Thoughts following Michael Guralnick’s 2023 paper on design of early child and family support

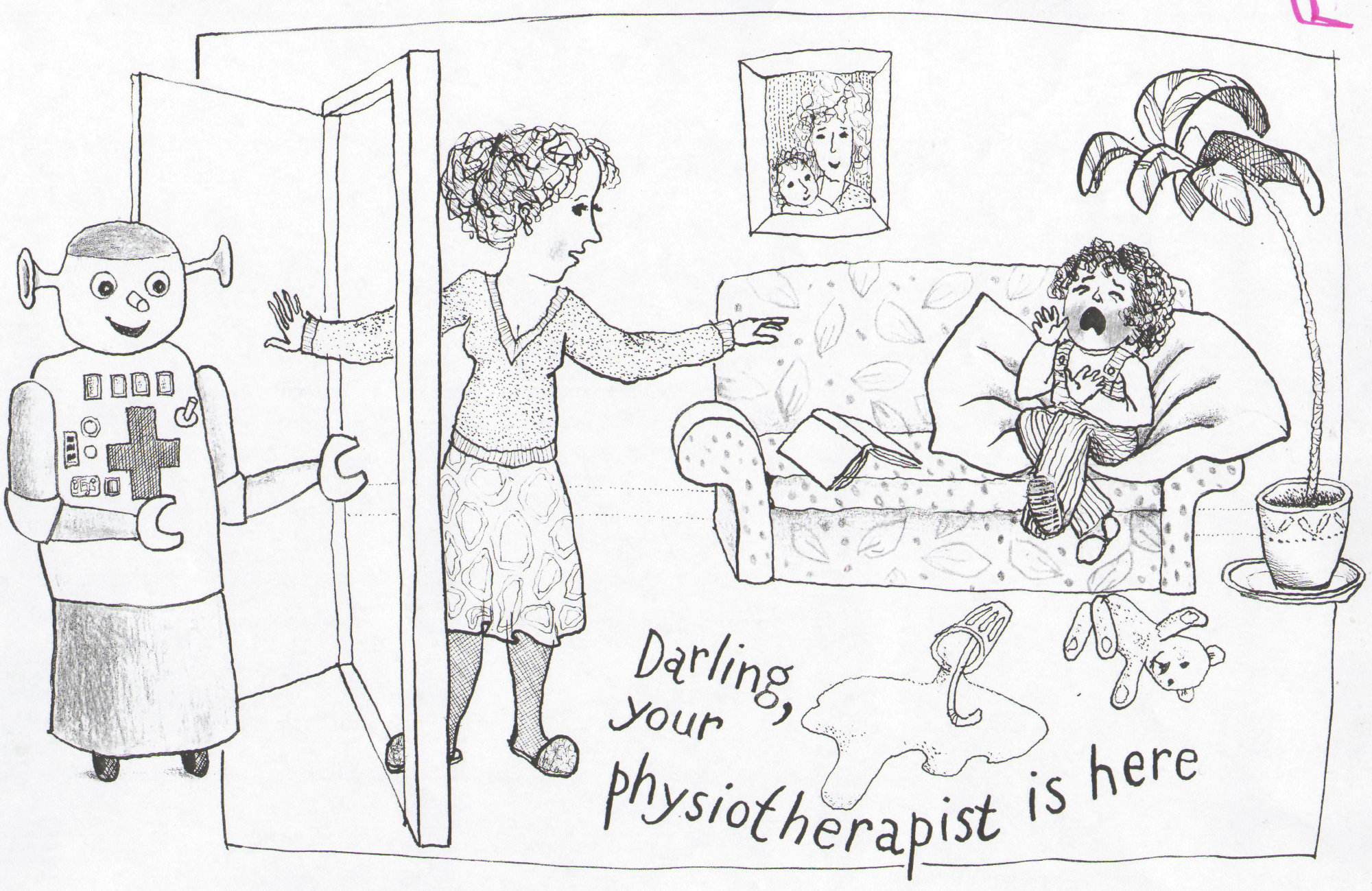

‘Designing an integrated system is one thing, getting professionals to be happy and secure working in it is another’

Michael Guralnick’s paper: A framework for the design of inclusive community-based early childhood intervention programs: infants and young children.

Editorial comment

The central theme -

‘...of this article is that major practice and policy advances in the field of early childhood intervention can be achieved through the application of a framework that systematically integrates developmental science, intervention science, and implementation science.’

The paper focuses on ‘...children who are at risk and those with established delays or disabilities and their families...’

These babies and young children are a relatively new focus for education, health and social care professionals and academics since the middle of the last century. Health has led the field with education, psychology and social care following a long way behind. When I began supporting babies and infants and their families in the 1980s, there were often good efforts to support the children (but on a patchwork basis), but almost no recognition of parent and family needs.

[See: When the Bough Breaks: An independent survey into families’ perceptions of One Hundred Hours keyworker service (1994)]

Guralnick’s authoritative paper shows how far we have come in some parts of some countries to remedy that lack. But now there is another necessary stage of development; to recognise, acknowledge and cater for the needs of the professionals around these children in what is a relatively new and extremely demanding workplace. My view is that we are still in the starting blocks in the effort to provide integrated, effective and equitable child and family support systems in any country. I cannot think of any examples. Perhaps a major contributory factor is the persistent neglect of the practical and emotional needs of the workforce.

Professor Guralnick’s paper is an important reflective and aspirational boost to the effort to respond to those babies and infants who invite us to radically rethink how we design and staff hospitals, schools and community supports for children and families. This comment on the paper is intended to contribute to this effort, adding my thoughts to Guralnick’s. My headings are:

-

professionals as human beings

-

professionals' attitudes to being joined up in horizontal teamwork

-

how the academic world has so far failed children and families

Preamble

I want to suggest that, in this field particularly, science and humanity must be in balance. The birth of a baby with problems, or the emergence of problems in the months afterwards is of tremendous significance to (most) families. Parents typically say no news could be more significant, more worrying or of greater impact on their family. A direct consequence of this is that the first professionals that come along to help are meeting a family who are probably very vulnerable and fearful. The perceptive professional (doctor, nurse, fieldworker, keyworker, ‘therapist’, teacher...) will see two different and connected sets of needs: firstly, for the child’s survival, health, development, wellbeing, and freedom from pain. Secondly, for the emotional and practical needs of the family as they gradually adjust to the new situation they find themselves in.

[See:The Keyworker: a practical guide (in family support)]

There is potential here for a turmoil in which there is everything that is most human: trauma, pain, nightmare, disappointment, anxiety and guilt mixed with love, joy, hope and dreaming. Being with a family at this time in a professional role is not a scientific activity. Regardless of a particular professional’s skills, parents will value seeing the basic human qualities of warmth, friendliness, concern, compassion and genuineness. The capacity to be human in this way is a basic requirement for all professionals in early child and family support. If we cannot show this humanity, we will not be able to help families very much whatever our scientific training.

Professionals as human beings

Professor Guralnick tells us, ‘Within the DSA [Developmental Systems Approach], these risk factors are organized in terms of components comprising the personal characteristics of the parents/caregivers....’. I argue that any early child and family support system must also acknowledge, respect and adapt to the personal characteristics of the people in the workforce. We can then:

-

provide training and supervision for professionals who can do the science but not the humanity leaving families with extensive unmet needs

-

intervene when a professional is letting work concerns take over their life and who, in the face of extreme child and family needs, is becoming overwhelmed by anxiety, guilt, a sense of inadequacy and is approaching burnout.

Professionals' attitudes to being joined up in horizontal teamwork

I characterise the flat power structures of multiagency, multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary integration as horizontal teamwork in which professionals from various agencies (and parents of course) treat each other as equals. This mutually respectful workplace is in contrast to the vertical hierarchies of most public and private organisations and institutions in which everyone has a boss above and, probably, underlings below.

[See: Horizontal Teamwork in a Vertical World: Exploring interagency collaboration and people empowerment]

Speaking of the aspiration for a well-defined and integrated system, Guralnick says, ‘Unquestionably, this is a long-term process that will require extraordinary effort, a seemingly unprecedented level of cooperation among all involved....’ This is a gross understatement in my experience. Even the straightforward professional collaboration needed at the grassroots for such an uncomplicated horizontal model as Team Around the Child (TAC) often proves impossible to achieve.

[See: TAC for the 21st Century: Nine essays on Team Around the Child.

Facilitating professional multiagency and multidisciplinary cooperation brings us straight back to the issue of personal characteristics of the people in the workforce. Designing an integrated system is one thing, getting professionals to be happy and secure working in it is another. Too often, basic emotions, protection of status and even snobbery are involved when professionals are required to work closely together, to share information and to trust each other’s observations and assessments. In my long experience, negative personal characteristics and basic human feelings can get in the way of aspirational transdisciplinary approaches around children and families.

[See: Transdisciplinary teamwork gets 'up close and personal'. Is that why we are afraid of it?

Quoting from Horizontal Teamwork in a Vertical World (2012):

‘This obstacle to interagency collaboration has to be respected and addressed in careful design of the horizontal structure, fastidious attention to the maintenance of high professional standards, and the provision of initial and on-going training and proper supervision. Experience shows that practitioners are not going to become comfortable and competent in horizontal teamwork overnight just because a new system has been imposed.’ (p 64).

This publication has a comprehensive list of tasks for managers who want to make the horizontal landscape a welcoming, rewarding and safe workplace for professionals.

How the academic world has so far failed children and families

My experience is that academics have historically wanted to sidestep the whole issue of multiagency, multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary integration in their research and teaching. Perhaps this is no surprise given the history of separate schools and departments in universities and the requirement for academics to inhabit ever deeper silos. As long as integration is an academic anathema, there will be very few graduates competent in collaborative teamwork. I explored this deplorable situation in UK and Ireland before the pandemic. I wonder what the situation is in your country.

[See: Integration research effort interrupted by the pandemic ]

Finally

As a graduate scientist and teacher of many decades, I have deep respect for the mystery of how children develop and learn, often making good progress in the direst of circumstances and with the most challenging conditions and impairments. While we need the best science we can get, we must keep a sense of mystery and awe.

There is not a mystery to be solved here. Rather, it is an invitation to all of us in this very special world of care, health and education*, to keep science, humanity and humility working in harness with each other in the best interests of new children, families and the professionals around them.

[* For my definition of education in the context of early child and family support, see: Education, Health and Development: Towards shared language and practice around babies and infants who have a multifaceted condition. A teacher’s view]

Peter Limbrick, September 2023.

Image copyright M Jirankova-Limbrick 2017 (This was drawn for TAC Bulletin and also used in Bringing up babies and young children who have very special needs)

Comments welcome. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Also see: Systems theory promoting early child development programmes. Perhaps it is all about pastry!